The Winter Alchemist | How History Transformed A Bishop Into The Spirit Of Christmas

The story of Christmas and Santa Claus is not merely a timeline of dates or a list of commercial milestones. It is a two-millennium-long love story between humanity and the idea of hope. It is the history of how we have sought to bring light into the darkest, coldest nights of the year through the alchemy of generosity, folklore, and the sanctification of the home.

The historical trajectory of the relationship between Christmas and the figure of Santa Claus represents one of the most complex syntheses of hagiography, folklore, social engineering, and commercial iconography in Western civilization. Far from being a static entity, the figure known as Santa Claus is a multifaceted construct that has evolved over nearly two millennia, shifting from a fourth-century Greek bishop to a nineteenth-century American domesticator of rowdy festivals, and finally to a global commercial ambassador.

This evolution is inextricably linked to the history of Christmas itself—a holiday that has transitioned from a strictly liturgical observance and a season of pagan-inflected “misrule” into a child-centric, family-oriented, and highly commercialized event. The intersection of Saint Nicholas of Myra and the midwinter feast reflects broader societal changes in the perception of childhood, the role of the home, and the secularization of sacred symbols.

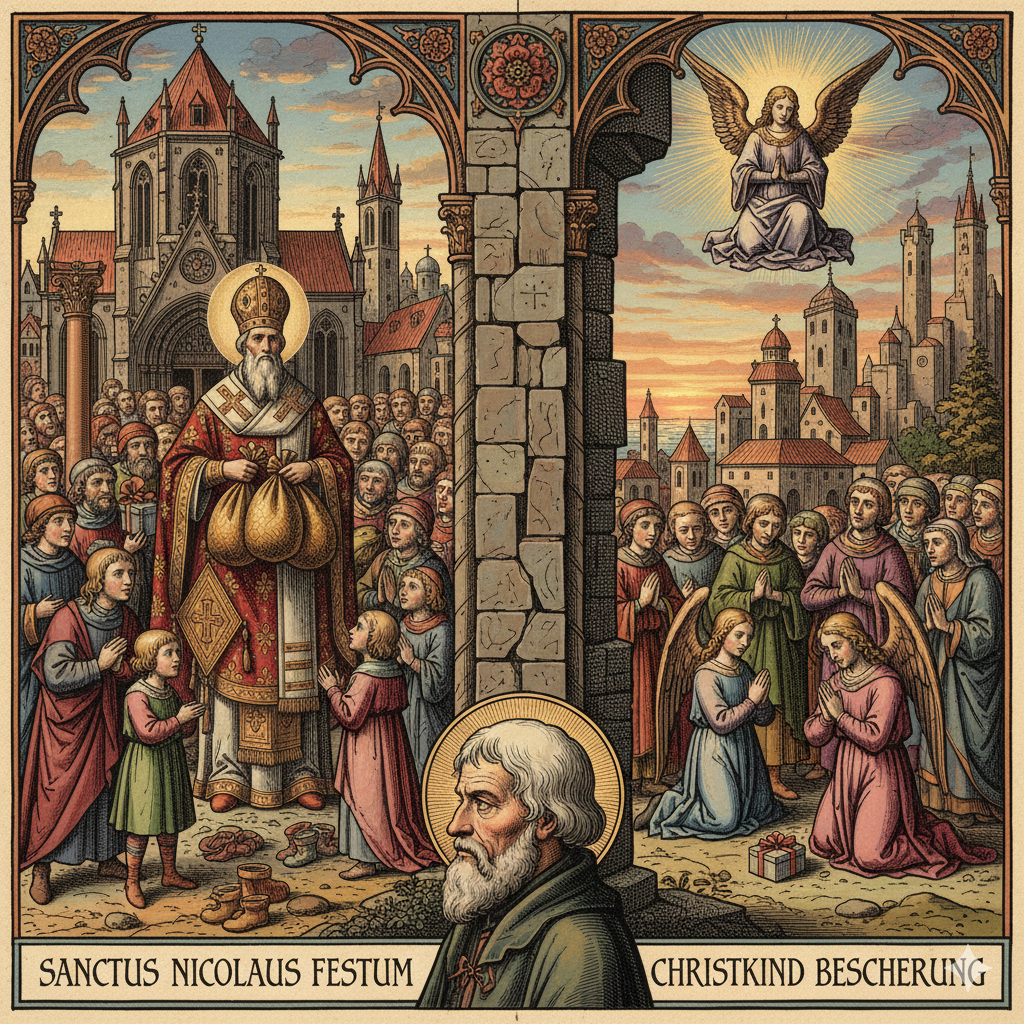

Saint Nicholas of Myra

Before he was a resident of the North Pole, Santa Claus was a man of the Mediterranean. Born in the late 3rd century in what is now Turkey, Saint Nicholas was a figure defined by radical empathy.

His most famous act of grace—secretly tossing bags of gold through a window to save three daughters from a life of destitution—established the spiritual DNA of Christmas: the idea that the greatest gifts are those given in secret, expecting nothing in return. This act didn’t just provide a dowry; it provided a template for the “anonymous miracle.” When those bags of gold reportedly landed in stockings drying by the fire, the chimney and the mantle became forever hallowed ground.

The Archetype of the Anonymous Gift-Giver

Nicholas’s most enduring legend—and the one that directly informs the ritual of the Christmas stocking—concerns a father who had fallen into such dire poverty that he could not provide dowries for his three daughters. In the social context of fourth-century Asia Minor, a lack of a dowry frequently meant that young women would be forced into prostitution or slavery. Upon hearing of the family’s plight, Nicholas went to their house under the cover of darkness and secretly tossed bags of gold through an open window. Legend suggests that on at least one occasion, the gold landed in stockings or shoes that the daughters had left by the fireplace to dry, creating the functional template for the modern gift-delivery mechanism. This act of charity was performed anonymously to preserve the father’s dignity, a characteristic that remains central to the Santa Claus mythos today.

The Expansion of Patronage & Miracles

As the Bishop of Myra, Nicholas became a figure of immense popularity in both the Eastern and Western Churches. His reputation for piety was such that legends claimed he began fasting as an infant, refusing to breastfeed on Wednesdays and Fridays. He was also a participant in the profound theological struggles of the early Church, reportedly attending the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, where he allegedly struck the heretic Arius in the face—though historical records of the council’s attendees do not definitively list his name. Beyond his charity, Nicholas was credited with a variety of miracles that reinforced his status as a “Wonderworker”.

One of the more graphic medieval legends involves Nicholas resurrecting three children who had been murdered by a malevolent innkeeper during a famine. The innkeeper had allegedly butchered the children and placed them in a tub of brine to be sold as pork, but Nicholas discovered the crime and restored the boys to life. This story solidified his role as the primary protector of children and explains why his feast day, December 6, became a major child-centered holiday in Europe.

The Medieval Liturgical Calendar & the Boy Bishop

During the middle Ages, the relationship between Saint Nicholas and the winter season was liturgical rather than strictly seasonal. His feast day on December 6 fell during the season of Advent, a period of preparation for the birth of Christ. In much of medieval Europe, the celebrations on December 6 were more significant for children than the celebration of Christmas itself.

The Tradition of the Boy Bishop

One of the most elaborate medieval customs associated with Saint Nicholas was the tradition of the “Boy Bishop”. Between the feast of Saint Nicholas and the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28, a young boy would be elected by his peers to dress in the full regalia of a bishop and preside over various church functions. This custom was a form of “social inversion” or “misrule,” where the least powerful members of society—children—were given authority, reflecting the humility associated with Nicholas and the arrival of the Christ Child. This tradition was widely supported by monarchs like Henry VII, though it was later banned by Henry VIII during the Reformation as part of his efforts to suppress saintly veneration.

Relics and the Spread of the Cult

The fame of Saint Nicholas was further amplified in 1087 when Italian merchants stole his remains from Myra and brought them to Bari, Italy. This “translation” of the relics made Bari one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Europe and ensured that Nicholas’s reputation for generosity and miracles spread to the Western Church. By the Renaissance, he was arguably the most popular saint in Europe, serving as the patron of sailors, merchants, pawnbrokers, and children.

The Reformation & the Secular Divergence

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century created a profound crisis for the Saint Nicholas tradition. Reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli sought to abolish the veneration of saints, which they viewed as a “popish” distraction from the direct worship of God. Consequently, the public celebration of Saint Nicholas Day was suppressed in most Protestant regions.

The Invention of the Christkind

To maintain a gift-giving tradition while removing the saintly intermediary, Martin Luther promoted the idea of the Christkind (Christ Child) as the bearer of presents. Luther’s intent was to shift the theological focus away from a human saint and toward the gift of Christ’s birth. This shift also necessitated a change in the date of gift-giving, moving it from December 6 to the Feast of the Nativity on December 25.

Over time, the Christkind evolved in the popular imagination into a fairy-like, golden-haired figure, particularly in German-speaking countries. When German immigrants brought this tradition to the United States, the name Christkindlein (Little Christ Child) was eventually Anglicized into “Kris Kringle”. By the 19th century, “Kris Kringle” had become synonymous with Santa Claus in the American consciousness, despite its original intent to replace the saint-like figure altogether.

The Dutch Preservation| Sinterklaas

While much of Northern Europe abandoned Saint Nicholas, the Netherlands was a notable exception. Despite the Reformation, the Dutch continued to celebrate Sinterklaas (a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas). The Dutch Sinterklaas retained many of the bishop’s original attributes: he was portrayed as a tall, lean man in red bishop’s robes, wearing a miter and carrying a jeweled staff.

The Dutch tradition also introduced unique folkloric elements that would later influence the American Santa:

- The White Horse: Sinterklaas rode a white horse over the rooftops of houses.

- The Shoes by the Chimney: Children left wooden shoes (klompen) by the chimney, filled with hay or carrots for the horse, hoping for treats in return.

- Zwarte Piet (Black Pete): A companion who assisted the saint and carried a bag to punish naughty children.

- Arrival from Spain: Unlike the modern Santa from the North Pole, the Dutch believed Sinterklaas traveled from Spain by boat each year.

British Folklore & the Personification of Winter

In England, a separate lineage developed that was largely independent of the Saint Nicholas hagiography. This figure, known as Father Christmas, was originally a personification of the “spirit of winter” and festive cheer rather than a specific gift-giver.

The Medieval Spirit of Good Cheer

The early precursors to Father Christmas included figures like “Sir Christmas” or the “Lord of Misrule,” who presided over the twelve days of Christmas festivities. These characters were typically associated with adult entertainment, feasting, and drinking rather than children or gift-giving. In Ben Jonson’s 1616 play Christmas, His Masque, a character named “Old Christmas” appears with a long white beard and children named “Misrule,” “Carol,” and “Mince Pie,” representing the personified essence of the holiday’s traditional customs.

The Puritan Ban & the Royalist Icon

The relationship between Christmas and Father Christmas became politically charged during the English Civil War. The Puritan government, viewing Christmas as a pagan survival and a source of debauchery, attempted to abolish the holiday in the mid-1640s. Royalist pamphleteers responded by using “Old Father Christmas” as a symbol of “the good old days” of traditional hospitality and social harmony. Following the Restoration of 1660, Father Christmas returned as a nostalgic figure, often depicted in old-fashioned, out-of-date clothing to signify a connection to a merrier past.

The American Nexus| New York & the Invention of Tradition

The modern relationship between Christmas and Santa Claus was synthesized in 19th-century New York City. This period saw a deliberate effort by the city’s intellectual and social elite—the “Knickerbockers”—to redefine Christmas. At the turn of the century, Christmas in New York was a rowdy street festival characterized by public drunkenness and “wassailing,” where the lower classes would confront the wealthy for food and drink.

John Pintard & the New York Historical Society

John Pintard, an influential patriot and founder of the New York Historical Society in 1804, sought to establish Saint Nicholas as the patron saint of both his society and the city. Pintard promoted the Dutch heritage of New York (formerly New Amsterdam) as a way to create a distinct American cultural identity separate from British influence. In 1810, he organized the first St. Nicholas anniversary dinner and commissioned artist Alexander Anderson to create an image of the saint for the guests. Anderson’s portrayal still showed Nicholas as a religious figure, but it included stockings hanging by a fireplace, signaling the beginning of the saint’s transition into a domestic icon.

Washington Irving’s Satirical Transformation

In 1809, Washington Irving published A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty under the pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker. Although the work was a satire, Irving’s descriptions of “St. a Claus” had a profound impact on the legend. Irving was the first to describe Saint Nicholas as a portly, pipe-smoking Dutchman rather than a solemn bishop. He also introduced the idea of the saint flying over the city in a wagon and dropping presents down chimneys, effectively translating the Dutch Sinterklaas into an Americanized folkloric figure.

Clement Clarke Moore & the Narrative Blueprint

The definitive narrative connection between Santa Claus and Christmas was established by the 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” commonly attributed to Clement Clarke Moore. Written in 1822 for his own children, Moore’s poem achieved massive popularity after being published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel.

Moore’s poem provided the primary mythical details that define the holiday today:

- The Sleigh and Reindeer: Moore replaced Irving’s wagon with a “miniature sleigh” pulled by “eight tiny reindeer,” whom he named Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder, and Blixen.

- Physical Description: He described St. Nick as a “jolly old elf” with twinkling eyes, rosy cheeks, and a round belly that “shook when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly”.

- The Timing of Arrival: Critically, Moore placed the saint’s arrival on “the night before Christmas” rather than December 6. This shift decoupled the character from its Catholic feast day associations and made him the central figure of the domestic, family-centered Christmas Eve.

The Social History of Domestication| Stephen Nissenbaum’s Thesis

The transformation of Santa Claus was not merely a literary curiosity; it was a response to the social instability of the early 19th century. Historian Stephen Nissenbaum, in The Battle for Christmas, argues that the modern Christmas was “invented” as a way to domesticate a rowdy holiday and maintain social order.

From Street Riots to Family Rooms

In the early 1800s, the growing urban population in New York and Philadelphia led to Christmas celebrations that often turned into gang violence and riots. The upper classes sought to “tame” the holiday by moving the celebration off the streets and into the secure confines of the family home. By creating a myth centered on a secret visitor who brought gifts to children, the Knickerbockers shifted the focus of Christmas from adult revelry to childhood innocence.

Santa as a Moral Disciplinarian

The “naughty or nice” list served as a mechanism for parental control. In some early 19th-century depictions, Santa was even portrayed as a disciplinary figure; one 1870 cartoon by Thomas Nast showed him jumping out of a jack-in-the-box with a switch for spanking naughty children. Over time, however, the more punitive aspects of the legend—inherited from European figures like Krampus—were softened, and Santa became a purely benevolent figure who incentivized good behavior through the promise of rewards.

Thomas Nast & the Visual Standardization

While Moore provided the narrative, the artist Thomas Nast provided the visual architecture of the modern Santa Claus. A political cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, Nast produced 33 Christmas-themed illustrations between 1863 and 1886 that defined Santa’s appearance and mythology for a national audience.

Santa as a Patriotic Symbol

Nast’s first depiction of Santa Claus appeared in the January 3, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly, titled “Santa Claus in Camp”. To boost Union morale during the darkest days of the Civil War, Nast portrayed Santa visiting Union soldiers and distributing gifts. Notably, Santa was dressed in a suit patterned with stars and stripes. This use of Santa as a Union supporter helped nationalize the character, transforming him from a New York Dutch localism into a symbol of American national unity.

The Invention of the North Pole & the Workshop

Nast was responsible for several key additions to the Santa Claus legend that had not existed previously:

- The North Pole: Nast was the first illustrator to locate Santa’s home at the North Pole. This was a strategic choice; in the 1860s, the North Pole was a largely unexplored region that belonged to no nation, allowing Santa to become a universal symbol of goodwill that both the North and the South could embrace after the war.

- The Toy Workshop and Elves: In his 1863 illustration “Santa Claus and His Works,” Nast introduced the idea of Santa’s workshop where he and his elf assistants hand-crafted toys. This countered the growing industrialization of the era by emphasizing the sentimental, handmade nature of Christmas gifts.

- The Account Book: Nast formalized the bureaucracy of Christmas by showing Santa recording children’s behavior in an enormous ledger.

- Physicality and Color: Nast transitioned Santa from Moore’s “tiny elf” to a full-sized, portly man with a thick white beard. While Santa had appeared in various colors previously (including tan and green), Nast’s later work consistently used the red, fur-trimmed suit that became the global standard.

The Commercial Era| Coca-Cola & the Globalization of Santa

By the early 20th century, Santa Claus was a staple of American culture, but his appearance remained somewhat fluid until the Coca-Cola Company intervened in 1931. Seeking to promote soda consumption during the winter months, Coca-Cola commissioned illustrator Haddon Sundblom to create a “wholesome” and “human” Santa Claus.

Haddon Sundblom’s Humanized Icon

Sundblom’s paintings, which appeared annually until 1964, moved away from the more fantastical or elfin depictions of the 19th century. He used Clement Clarke Moore’s poem as his primary inspiration, creating a Santa that was “warm, friendly, pleasantly plump, and human”. Sundblom used real people as models, including his retired salesman friend Lou Prentiss and later himself.

The impact of the Sundblom campaign included:

- Relatability: Santa was shown in mundane, human moments—raiding the refrigerator for a turkey leg, hushing a family dog, or playing with toys he was supposed to deliver.

- Standardization of Attire: While Santa had appeared in red since the 1870s, the ubiquity of Coca-Cola’s mass-media advertising solidified the specific “velvety red suit with white fur trim” as the absolute standard.

- Secondary Characters: Sundblom introduced the “Sprite Boy” in the 1940s, an elf character who accompanied Santa in ads (though not related to the beverage Sprite, which launched later).

- A Familiar World: The advertisements created a consistent narrative world for Santa that felt grounded and real, encouraging families to leave out treats (and Coca-Cola) for him on Christmas Eve.

The Response of the Public

The public became so invested in Sundblom’s version of Santa that they would write letters to the company if any details were incorrect. In one instance, when Sundblom painted Santa without a wedding ring, fans wrote in asking what had happened to Mrs. Claus. In another, his belt was painted backwards—a result of Sundblom using a mirror as a model—leading to further scrutiny from the audience. This level of engagement demonstrated that Santa had transitioned from a folkloric character into a quasi-real member of the American family.

The Merger of Father Christmas & Santa Claus in Britain

While the American Santa Claus was being defined, the British Father Christmas was undergoing a similar transformation. Throughout the mid-19th century, the two characters existed as distinct figures: Father Christmas as the spirit of adult feasting, and Santa Claus as the magical bringer of children’s gifts.

The Victorian Child-Centric Turn

As Victorian Christmas traditions evolved to focus on the home and family, Father Christmas began to adopt the attributes of the American Santa. By the 1870s and 1880s, the custom of hanging stockings and the arrival of a nocturnal visitor became established in Britain. By the early 20th century, Father Christmas had abandoned his green robes and crown of holly in favor of the red, fur-trimmed suit and the sleigh.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Letters from Father Christmas, written between 1920 and 1943, represent the final synthesis of these traditions. Tolkien’s character, whom he sometimes referred to as “Father Nicholas Christmas,” lived at the North Pole with elves and polar bears, explicitly linking the medieval saint with the modern personification of the holiday.

Dark Shadows| The Malevolent Companions of Christmas

The relationship between Christmas and its gift-bringers is not entirely one of light and joy. Many European traditions have preserved a “shadow” side to the legend, featuring malevolent characters who accompany the saint to provide a darker balance to his generosity.

The Role of Punishment

- Krampus: In the Austro-Bavarian tradition, Krampus is a horned, anthropomorphic figure who punishes naughty children by swatting them with birch rods or carrying them away in a sack.

- Père Fouettard: In French folklore, this figure is said to be the innkeeper who murdered the three children Nicholas resurrected; as penance, he must follow the saint and whip disobedient children.

- Knecht Ruprecht: In Germany, he serves as St. Nicholas’s farmhand, carrying a bag of ashes to hit children who cannot say their prayers.

- These figures highlight the original moralistic nature of the holiday. While the American Santa Claus has largely shed these frightening associates, they remain a vital part of the cultural landscape in Europe, serving as a reminder of the consequences of “naughtiness”.

The Gift of Wonder

The evolution of Santa Claus shows that we never truly outgrow our need for magic. From a 4th-century Greek bishop to a 21st-century digital icon, Santa has survived by evolving alongside us. He is the personification of our best impulses—charity, joy, and the sanctity of the home.

“Even the most secularized versions of Christmas are still fueled by the ‘vapors’ of ancient light.”

As long as there are children to dream and families to gather, the “Jolly Old Elf” will continue to fly, reminding us that the greatest gift we can give is a sense of wonder.